Paris and the GWSA: Resetting our Targets

The Paris Agreement

The recent Paris Agreement represents tremendous progress in the fight against climate change; countries around the world have agreed to take real action to limit warming to no more than 2°C (3.6°F) while making efforts to keep warming below 1.5°C (2.7°F). The 1.5°C goal is important; the mantra “1.5 to stay alive” started with small island nations that understand 2°C means disaster for low-lying countries. 2°C may also spell disaster for coastal cities like Miami and New Orleans, where rising seas associated with 2°C warming would inundate these cities by 2100. In short, the 2°C goal is inadequate to protect vulnerable communities from climate change—or as Naomi Klein writes, “It’s a target that is beyond reckless.”

The Paris Agreement is progress, but analysis of the non-binding nationally determined contributions (NDCs) made by each country as part of the Agreement shows they are insufficient; the NDCs on their own would leave us with warming of 3.5°C (6.3°F) by 2100. COP21 brought the world together to take action, but it’s not yet enough.

Climate Interactive—a non-profit run by Systems Dynamics experts associated with MIT—has modeled various global greenhouse gas (GHG) emission scenarios and outlined 2030 emission reduction requirements for both the 1.5°C and 2°C thresholds. 2030 is a critical date from a climate perspective; if we don’t cut emissions sufficiently by this point, taking the action necessary to curb emissions will become prohibitively difficult. Analysis from Climate Interactive shows the U.S. must reduce emissions by 60% from 2005 levels by 2030 to keep warming to 1.5°C, with a 45% reduction required if we’re willing to take our chances with 2°C. Current U.S. pledges aim for emission reductions of 26% by 2025, far from either target.

Massachusetts Goals Lacking

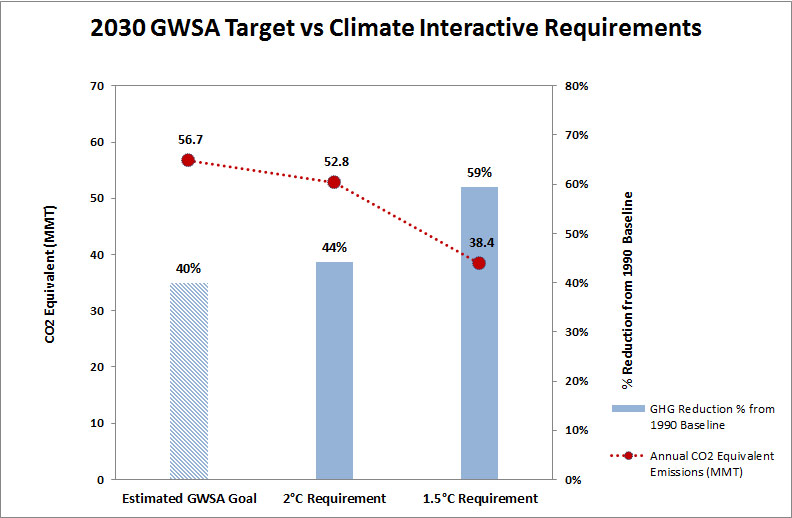

What does this mean for Massachusetts? If we look to our current (and legally binding) Global Warming Solutions Act (GWSA) emission reduction targets, we find they are not sufficient to meet either the 1.5°C or even the 2°C national targets. Although no firm 2030 GWSA target has yet been set, a recent bill passed by the state senate aims to set a “firm” 2030 reduction goal of 35-45% from 1990 levels. The high end of this range would keep Massachusetts in-line with the 2°C Climate Interactive targets—if the state attempts to reach it. The Climate Interactive reduction targets for 2°C and 1.5°C normalized to the GWSA 1990 baseline are 44.13% and 59.37% respectively.1

Comparison of a potential Massachusetts GWSA 2030 target with Climate Interactive requirements

Comparison of a potential Massachusetts GWSA 2030 target with Climate Interactive requirements

The good news is that the outer range of the 2030 proposal for the GWSA is nearly sufficient to meet the 2°C target. The bad news is that Massachusetts is efficient, environmentally progressive and has tremendous offshore wind potential that has yet to be tapped. If a state like Massachusetts can’t hit the 1.5°C reduction target for 2030 or even the 2°C target with certainty, how can we expect other states to do it?

A New Goal for 2030

Massachusetts should take the bold and necessary step of setting a goal for 2030 commensurate with the need: a 60% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions (using the GWSA 1990 baseline) by 2030. Anything less and we resign ourselves to 2°C warming—at best. Insufficient Massachusetts goals alone won’t push the U.S. over national emission limits, but this is an issue of commons. If every state limits its actions and goals to those that appear politically feasible, we have little hope of keeping warming below even 2°C without federal regulation. And hoping for federal intervention is not an ideal contingency plan given the partisanship and proliferation of science doubters and deniers in Congress. States like Massachusetts must lead.

A strong 2030 emission goal for Massachusetts is an opportunity—a chance to boost the economy, create jobs and improve resiliency by generating electricity with regional renewable resources and improving the efficiency of our building and transportation sectors. A study by Synapse Energy Economics modelled policies required to reach a 40% reduction of emissions by 2030 for states that participate in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). These policies resulted in lower energy costs and thousands of new jobs for participating states. A 60% reduction will almost certainly yield greater economic benefits, but this scenario needs to be modelled in order to demonstrate feasibility and a path to implementation. We must show that not only is a 60% reduction goal necessary, it’s possible and beneficial.

________________________________________

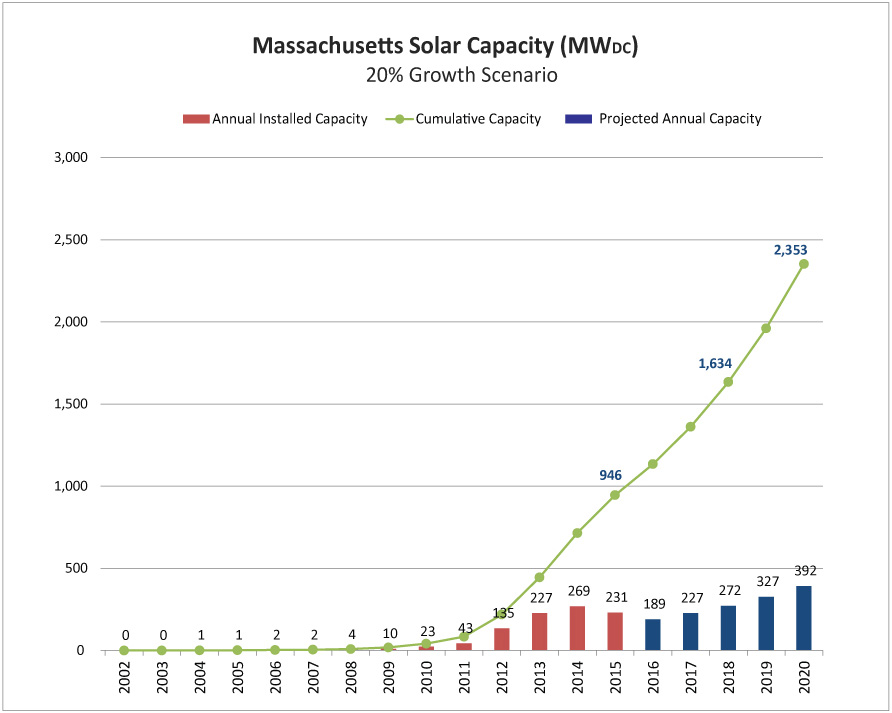

Massachusetts Solar capacity projections assuming 20% annual growth from 2016 to 2020.

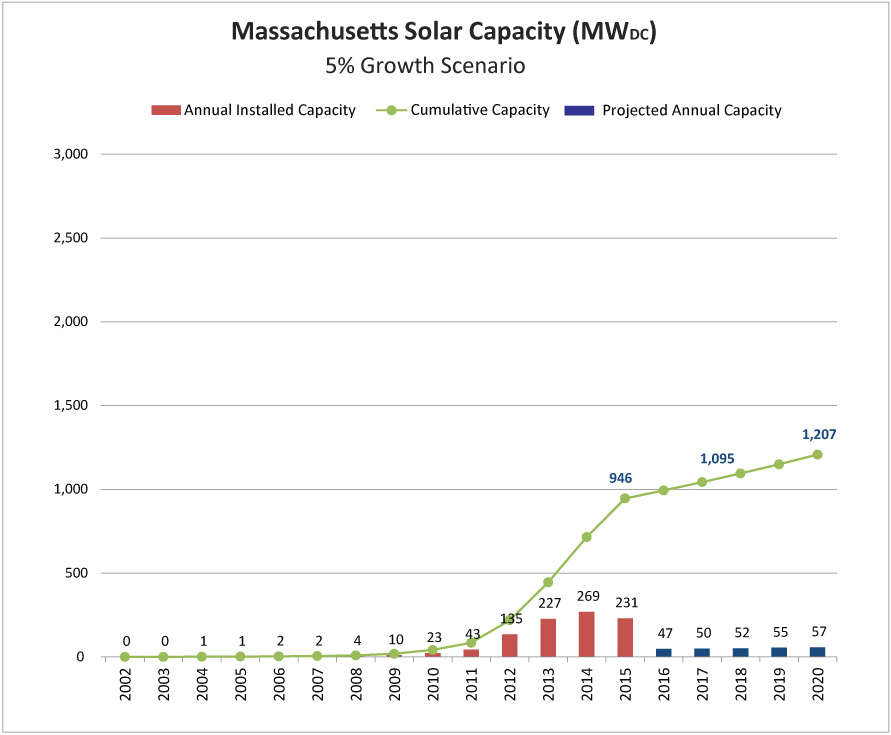

Massachusetts Solar capacity projections assuming 20% annual growth from 2016 to 2020. The “Nevada” Scenario: Massachusetts solar capacity projections assuming 5% annual growth from 2016.

The “Nevada” Scenario: Massachusetts solar capacity projections assuming 5% annual growth from 2016.