MPG for homes? Not yet.

If I had penny for every time I heard someone use the “MPG for homes” analogy in the energy-rating world, I’d have gleaming copper gutters on my house. It’s a powerful comparison that I’ve used myself, since most people are familiar with and trust (Volkswagen aside) the EPA’s fuel ratings for automobiles. If you’re anything like me, then you rely on MPG ratings to make buying decisions, which is one of the reasons the Volkswagen manipulation scandal was so disturbing. Our trust was shaken.

If we want to create an MPG for homes, it needs to be trustworthy. This is not easily accomplished, as accurately assessing the energy efficiency of a home is surprisingly difficult. Traditionally, we have relied on asset (i.e. home structure) ratings like RESNET’s Home Energy Rating System (HERS) and the DOE’s Home Energy Score (HES). These scores use complex energy modelling software and detailed in-person assessments of homes to generate scores that reflect efficiency. As these systems rely on human input and models—neither of which are 100% accurate—they aren’t perfect, but they are the best we currently have, at least for assessing structural efficiency.

Unfortunately, the effort and costs associated with in-person assessments have prevented these traditional asset ratings from scaling rapidly. In response, a number of organizations have tried to develop inexpensive and scalable scores derived from public record data. The ability to assess homes at scale using this data was the goal of research initiated by Kate Goldstein and Michael Blasnik, but their intention was to identify homes that had a high probability of being good efficiency retrofit candidates. This idea is now being applied to the real estate market.

The highly respected Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) recently released a report titled “An MPG for Homes” which explores the use of market forces to promote residential efficiency. I highly recommend reading it. The report highlights recent developments in the use of public record scores on some of the largest real estate portals in the United States. RealEstate.com (owned by The Zillow Group) and Redfin now showcase public record scores developed by Utility Score and Tendril respectively, and Utility Scores will soon be accessible on Zillow, making public record scores available for millions of homes. The hope is that sharing these scores will encourage homeowners to make purchasing decisions based on efficiency, just like the MPG rating for cars.

How do they work?

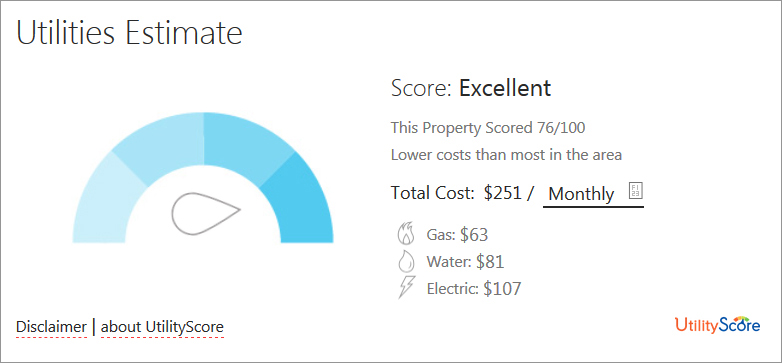

The two largest players in this space—Utility Score and Tendril1—use energy models and data based primarily on public records (e.g. tax assessment and real estate data) to estimate energy consumption and costs for a given home. These estimates are then used to generate a score between 1 and 100, where 100 represents homes with the lowest energy costs.

Utility Score on RealEstate.com (image credit: http://www.realestate.com)

Utility Score on RealEstate.com (image credit: http://www.realestate.com)

Public record scores do not require an on-site visit and are calculated programmatically, which drastically reduces cost and increases scale. Utility Score alone has calculated scores for 84 million single-family homes—over 70% of all occupied homes in the U.S. This is far beyond the approximately 1.8 million homes scored with HERS and HES to date.

The RMI report states that “the availability of this data will have an immediate positive impact for consumers,” and cites a study that finds 81% of people who expect to buy a new home in the next 2 years believe that energy efficiency “would cause them to choose one home over another.” This research implies that sharing efficiency scores can have a real impact, but what happens if the scores shared aren’t accurate?

The problem

I’ve analyzed public record scores for thousands of homes, and found only the weakest of correlations between these scores and established asset assessments like HERS and HES. Although my analysis has not focused on Utility Score or Tendril, I’m certain they are only slightly more accurate than throwing darts for any given home. 2

How can I be so sure? Because the inputs to the energy models are lacking for most homes. The public record data used to generate these scores is not always reliable, and there simply isn’t enough detail in the data—even if it were clean—to generate a score with consistent “MPG” accuracy. Inadequate data necessitates assumptions in the models that may align with regional trends, but results in poor marksmanship for individual homes. For example, without good data we have to guess at the levels of insulation in a home based on its construction year, location, or other factors. We’re able to make an educated guess (Tendril calls these “smart defaults”) by looking at what similar homes in that region typically have, but we don’t usually know how much insulation a particular home has (or how well it was installed). Since insulation is a key driver of energy consumption, just this one data point can sink the accuracy of a score. We then repeat this process for HVAC efficiency, air leakiness, window types—you get the idea. Mix in some incorrect building size and age data, and it becomes clear that we’re not likely to see accurate scores for most homes.

It’s not the models used by these organizations that are the issue, it’s the lack of accurate information we have on specific homes. These scores can provide reasonable approximations of energy efficiency for homes that match their assumptions, and this may occur for a significant percentage of homes. The underlying research behind the model defaults combined with the glacial pace of efficiency improvements in the housing stock help assure this. If home size and year constructed in the public record data are accurate and most other model assumptions align with reality, a public record score can hit the bullseye. Unfortunately, this is not likely to happen consistently enough to maintain consumer trust—especially when some individual scores miss the dartboard entirely.

Does it matter?

Like RMI, I want to see energy data on real estate listings. The idea is that disclosing energy information will lead to demand for efficient homes, which will encourage investments in home efficiency in a virtuous cycle. The isn’t just theory; academic researchers in the Netherlands found that homes that disclosed good energy scores sold for a 3.6% premium over similar homes with poor scores. As RMI states in their report, “homebuyers can use this information to compare homes and as a data point for negotiation with sellers.” It’s unclear what the long-term impact of sharing inaccurate scores might be, but there are three possible outcomes for individual homes today:

- A home receives a better score than it merits. Here a home is rewarded for fictional efficiency. The seller wins, as the house looks good on paper (or pixels), while the buyer potentially pays a premium for efficiency that doesn’t exist.

- A home receives a worse score than it merits. In this scenario, a home is not recognized for its efficiency and may sell for a discount because of this. The homebuyer gets a deal, while the seller may lose out.

- Finally, in some cases—when we have accurate data and most model assumptions match reality—a public record score will accurately reflect the efficiency of the home. Everybody wins, but this happens rarely enough that it becomes noise instead of feedback that drives demand for efficient buildings.

Homebuyers might trust the scores for some time (regardless of any disclaimers about accuracy), but may eventually devalue or ignore the scores altogether. It could prove difficult to win back consumer trust in the future when reliable scores are widely available.

It’s possible that disclosure of inaccurate scores on real estate sites will motivate owners of efficient homes to pay for a comprehensive asset rating like HERS or HES, which can be used to set the record straight. The end result might seem positive (more homes with reputable ratings), but what will be the effect of forcing homeowners to pay to correct a metric that was made public without their consent?

Alternatives

The idea of widely expanding the availability of home efficiency information on real estate sites is a good one, but the data we share should be reasonably accurate for all homes. Here are some alternatives to the public record model that sacrifice scaling-speed for accuracy:

- Make existing asset scores like HERS and HES visible in the real estate market. The Home Energy Labeling Information Exchange (HELIX) project aims to do just this by creating a central database that can store and provide certified asset ratings to local Multiple Listing Services (MLS) and real estate websites like Zillow and Trulia. This project will complement and streamline the work already being done by MLS across the country to expose home efficiency information.

HELIX inputs/outputs (image credit: www.neep.org)

- Increase the number of homes scored through local ordinances and legislation, like the bill proposed in Massachusetts that would require homeowners to disclose an approved asset score to potential buyers. The city of Portland Oregon has passed a similar ordinance, which requires disclosure of Home Energy Scores beginning January 1, 2018.

- Make sure every home that gets an energy audit has a reputable asset rating calculated as part of the assessment. It’s a missed opportunity to go into a home and gather nearly all the data needed to generate a score without actually producing one. This is a provision in the Massachusetts bill mentioned above.

- Share operational data (i.e. consumption and cost info from utility bills) and/or scores produced with this data instead of asset ratings. Disclosure of utility bill information to prospective homebuyers is already required in Alaska, Hawaii and Montgomery County Maryland, and has been done successfully in New York State and Chicago since 1987. This approach could scale rapidly if we had utility company cooperation, which admittedly is no small thing.

Although scores based on public record data are not accurate enough to provide a true MPG for homes, they do have value. For example, they can be used to estimate average residential energy consumption and costs for a particular region, identify homes that are likely to be good candidates for efficiency upgrades, or estimate the regional impact of weatherization efforts. These scores can be useful for planning and cost/benefit analysis, but not for influencing individual real estate transactions—at least not with the data we have available today.

RMI is right that we need to disclose energy information to homebuyers. Residential efficiency is not improving quickly enough, and we must leverage markets to create demand for efficient homes. It’s possible that public record scores will disrupt the market in a positive way, but there is real risk that we will do more harm than good by sharing scores that aren’t ready for mass consumption.

1 Update on December 11, 2017: Per RMI, Tendril has announced they are shutting down their public record energy scoring services.

2 I have compared HERS and Utility Scores for a small sample of efficient homes (i.e. where HERS index < 100). Although not a conclusive test, the results do support the dart analogy. Utility Scores are available for free at www.myutilityscore.com.

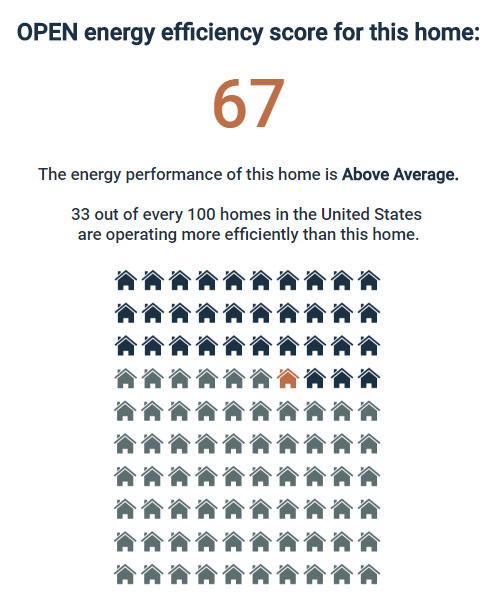

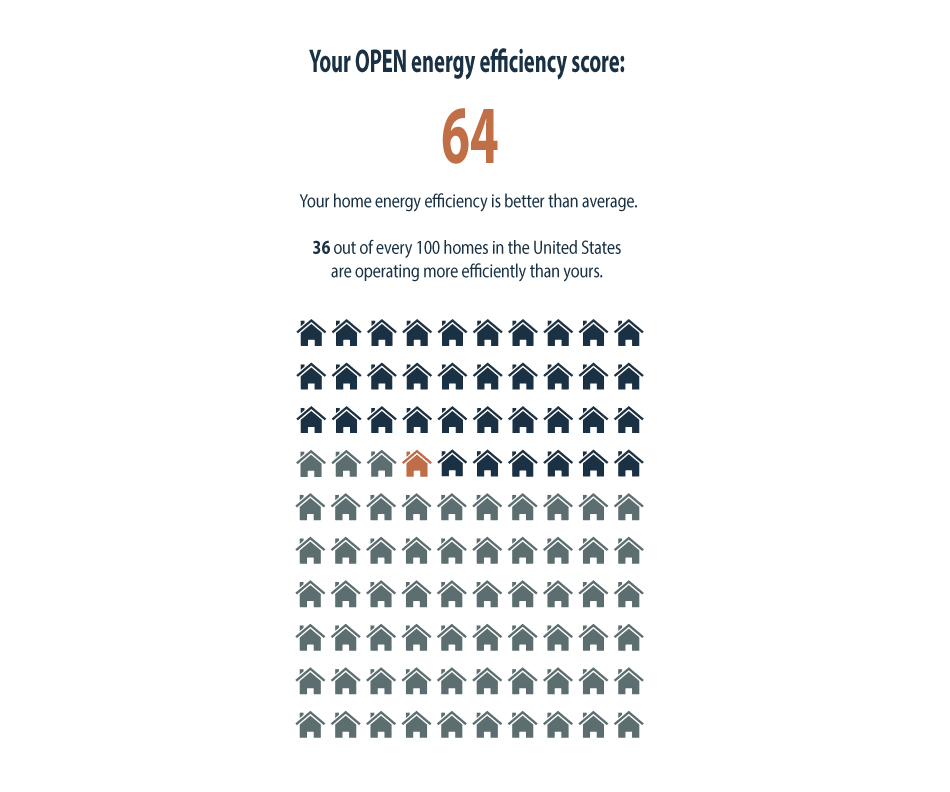

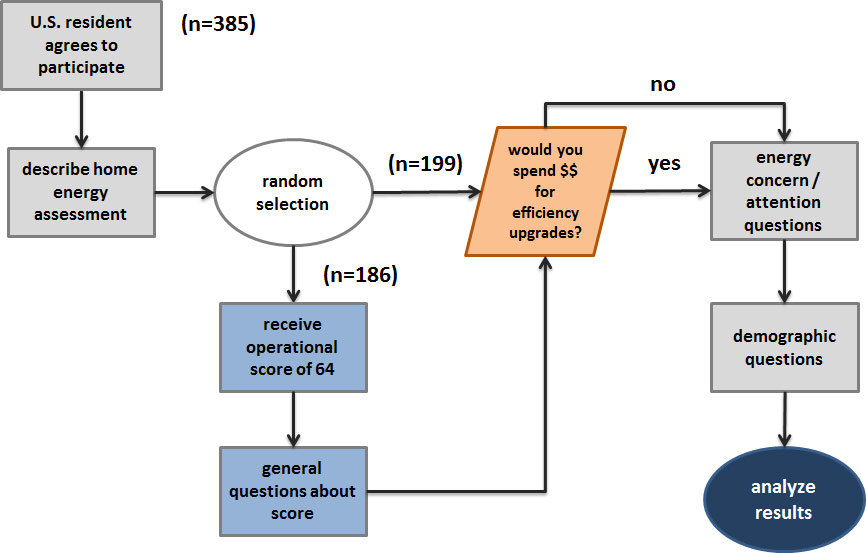

OPEN rating comparison graphic

OPEN rating comparison graphic

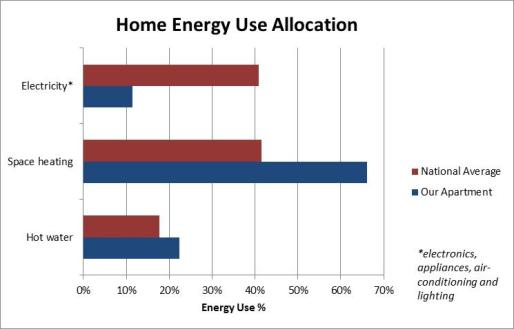

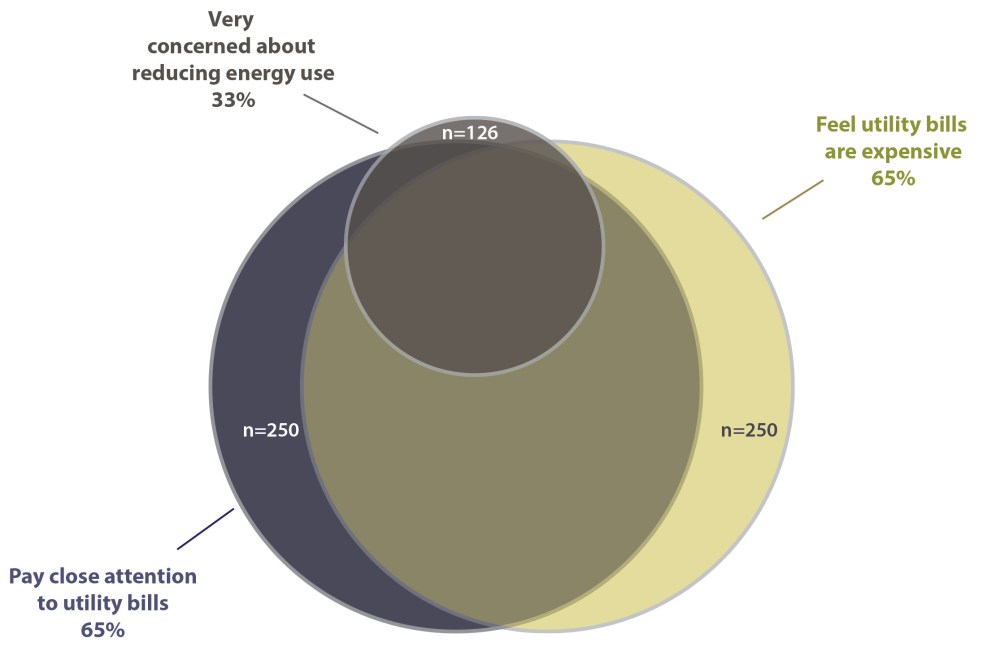

Breakdown of respondents concerned about their energy use

Breakdown of respondents concerned about their energy use